Welcome back to the fifteenth century. Our guides are a pair of Danish filmmakers who, in the 1920s, wrote and directed two carefully researched historical dramas. Their subjects exemplified the popular notion of the Dark Ages, a time when misguided authorities persecuted the poor in the name of righteousness. The first, Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan, is one of the first documentaries ever made, a study of the history of witchcraft and the Church’s retaliation against it. The second, Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (hereafter Joan), is one of those monoliths of film history that is so universally praised as to be difficult to approach, an intimate depiction of the trial and execution of the French heroine. Both films were controversial in their day, and almost a century later they appear at once alien and strikingly forward-thinking. Each has had an eventful afterlife, being released in a number of alternate versions over the decades. In their original forms, they paint a stark portrait of humanity.

Both Christensen and Dreyer open their films with statements of intent. The former states flatly that belief in witches and demons is the product of primitive superstition, which modern science has defeated. The latter expresses a wish to humanize an iconic figure, to show a simple peasant girl in the clutches of powerful men bent on destroying her. Immediately, the contrasting scopes of these projects are apparent. Häxan covers all of human history, while Joan restricts itself to a single day, not even covering the backstory of Joan’s accomplishments. There are social and political struggles at work in these stories as well as religious ones. In fact, it’s evident that neither filmmaker was especially interested in the finer points of theology. Still, there’s a noticeable difference in approach, with Christensen taking a condescending view of faith while Dreyer had nothing but sympathy for the pious girl who, as the title would indicate, was following in the footsteps of Christ.

Both Christensen and Dreyer open their films with statements of intent. The former states flatly that belief in witches and demons is the product of primitive superstition, which modern science has defeated. The latter expresses a wish to humanize an iconic figure, to show a simple peasant girl in the clutches of powerful men bent on destroying her. Immediately, the contrasting scopes of these projects are apparent. Häxan covers all of human history, while Joan restricts itself to a single day, not even covering the backstory of Joan’s accomplishments. There are social and political struggles at work in these stories as well as religious ones. In fact, it’s evident that neither filmmaker was especially interested in the finer points of theology. Still, there’s a noticeable difference in approach, with Christensen taking a condescending view of faith while Dreyer had nothing but sympathy for the pious girl who, as the title would indicate, was following in the footsteps of Christ.

Häxan follows the old educational structure “Tell them what you’re going to tell them; tell them; tell them what you’ve told them.” The first segment uses period artworks and models to explain the history of the supernatural, focusing on the things witches supposedly did and how religious authorities tried to identify and punish them. When subsequent sections of the film bring these scenes to life, Häxan almost functions as a primer on the new world of nonfiction feature films. A dry lecture suddenly gives way to some of the most lurid cinema ever created — nudity, lewdness, and torture abound. The use of stop- and reverse-motion special effects predates the Surrealists and remains startling today. Christensen himself plays the Devil in the film with shameless physicality. Through it all, the world of the imagination ends up being much more vivid than the truths the director prefers. Häxan has been called a horror-documentary hybrid. Like this year’s The Nightmare (another horror-doc, and the most recent film to scare the crap out of me), it’s partly about fears that are so strongly believed in that they become real.

Häxan follows the old educational structure “Tell them what you’re going to tell them; tell them; tell them what you’ve told them.” The first segment uses period artworks and models to explain the history of the supernatural, focusing on the things witches supposedly did and how religious authorities tried to identify and punish them. When subsequent sections of the film bring these scenes to life, Häxan almost functions as a primer on the new world of nonfiction feature films. A dry lecture suddenly gives way to some of the most lurid cinema ever created — nudity, lewdness, and torture abound. The use of stop- and reverse-motion special effects predates the Surrealists and remains startling today. Christensen himself plays the Devil in the film with shameless physicality. Through it all, the world of the imagination ends up being much more vivid than the truths the director prefers. Häxan has been called a horror-documentary hybrid. Like this year’s The Nightmare (another horror-doc, and the most recent film to scare the crap out of me), it’s partly about fears that are so strongly believed in that they become real.

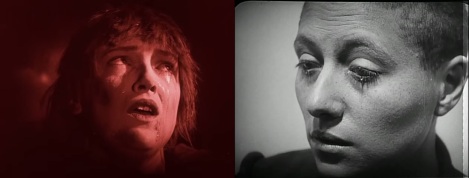

Joan doesn’t have the same obvious surface qualities to promote it. Famous for its unrelenting close-ups, this is the kind of masterpiece that isn’t content to be intellectually prized. It practically demands of its viewers the deepest, strongest feelings. The structure is simple enough. The judges question Joan, asking her to recant her blasphemy and repent of her cross-dressing. When she doesn’t, they threaten her with torture, then threaten her with death. The sight of an exhumed skull, along with her exhaustion and the repeated urging of the men towering over her, finally convince her to sign a confession, but she soon changes her mind and goes willingly to the stake. This process is depicted in tight close-ups and medium shots, with the camera sometimes panning over a row of leering accusers. Dreyer employs canted angles and accelerating cuts to make every moment feel decisive. The film rests on Renée Falconetti’s turn as Joan, possibly the most celebrated performance in film history. Her work is at once emotionally raw and uncanny. Her wide eyes seem to be in true communion with the divine, overwhelmed by revelation. Here, for once, cinema approaches the realm of the sacred. Counter-intuitively, it does so through a constant attention to the physical: tears, blood, the lines on faces.

Why were witches burned at the stake, beyond the obvious fear of their satanic powers? The word “witch” is never uttered in Joan. Whatever the shaky theological reasoning behind the verdict in Joan of Arc’s trial, the salient fact is that her judges were Burgundians, in league with the English in the Hundred Years’ War. Joan had inspired the French, had helped to turn the tide. So it was more of a sanctioned assassination. In Häxan, the misunderstanding of physical ailments is one cause of the scapegoating of witches. But what’s subtext in Joan becomes clear in Häxan: men have, historically, done ugly things to women. A young priest begins thinking impure thoughts when confronted with an attractive woman. Either she burns, or he will. Also significant is the class divide. Both films emphasize that the victims of these witch hunts were poor, couldn’t read, and were forced to respect the authority of those above them, even when they were accused of the most absurd things. Rulers maintained the status quo through fear — or at least, such was the modernist take on the era.

Why were witches burned at the stake, beyond the obvious fear of their satanic powers? The word “witch” is never uttered in Joan. Whatever the shaky theological reasoning behind the verdict in Joan of Arc’s trial, the salient fact is that her judges were Burgundians, in league with the English in the Hundred Years’ War. Joan had inspired the French, had helped to turn the tide. So it was more of a sanctioned assassination. In Häxan, the misunderstanding of physical ailments is one cause of the scapegoating of witches. But what’s subtext in Joan becomes clear in Häxan: men have, historically, done ugly things to women. A young priest begins thinking impure thoughts when confronted with an attractive woman. Either she burns, or he will. Also significant is the class divide. Both films emphasize that the victims of these witch hunts were poor, couldn’t read, and were forced to respect the authority of those above them, even when they were accused of the most absurd things. Rulers maintained the status quo through fear — or at least, such was the modernist take on the era.

The reality, as always, is more complex, and Joan overall does a better job of conveying that. Like The Night of the Hunter, Dreyer’s film shows us both true faith and hypocrisy and distinguishes between them. It’s a challenging reminder of how a persecuted class can develop into persecutors, and it’s a stirring expression of martyrdom. In Häxan, the witches’ sabbath is inaugurated by trampling on a cross; in Joan, an outwardly sympathetic cleric unknowingly steps on the shadow of a cross from which Joan had derived solace. The occlusion of a symbol of grace is unmistakable, but it’s also just a shadow. One can certainly find madness in Joan’s eyes rather than devotion. Christensen saw a simple link between the evidences for witchcraft and the symptoms of mental illness. Häxan‘s closing plea for greater awareness of mental health remains relevant. The original cut of The Passion of Joan of Arc, meanwhile, was for decades thought lost — consumed, like its heroine, in flames. Then, in 1981, a print was discovered in the closet of a Norwegian mental hospital. God is real.

The reality, as always, is more complex, and Joan overall does a better job of conveying that. Like The Night of the Hunter, Dreyer’s film shows us both true faith and hypocrisy and distinguishes between them. It’s a challenging reminder of how a persecuted class can develop into persecutors, and it’s a stirring expression of martyrdom. In Häxan, the witches’ sabbath is inaugurated by trampling on a cross; in Joan, an outwardly sympathetic cleric unknowingly steps on the shadow of a cross from which Joan had derived solace. The occlusion of a symbol of grace is unmistakable, but it’s also just a shadow. One can certainly find madness in Joan’s eyes rather than devotion. Christensen saw a simple link between the evidences for witchcraft and the symptoms of mental illness. Häxan‘s closing plea for greater awareness of mental health remains relevant. The original cut of The Passion of Joan of Arc, meanwhile, was for decades thought lost — consumed, like its heroine, in flames. Then, in 1981, a print was discovered in the closet of a Norwegian mental hospital. God is real.